What if a path to democratization shows itself long before the regime collapses? Transformations in Spain and Taiwan in the last century reveal how swiftly this can happen. Societies evolve, expectations rise, and a new generation begins to live in a world the old regime no longer understands. When that gap grows too wide, autocracy faces a natural death.

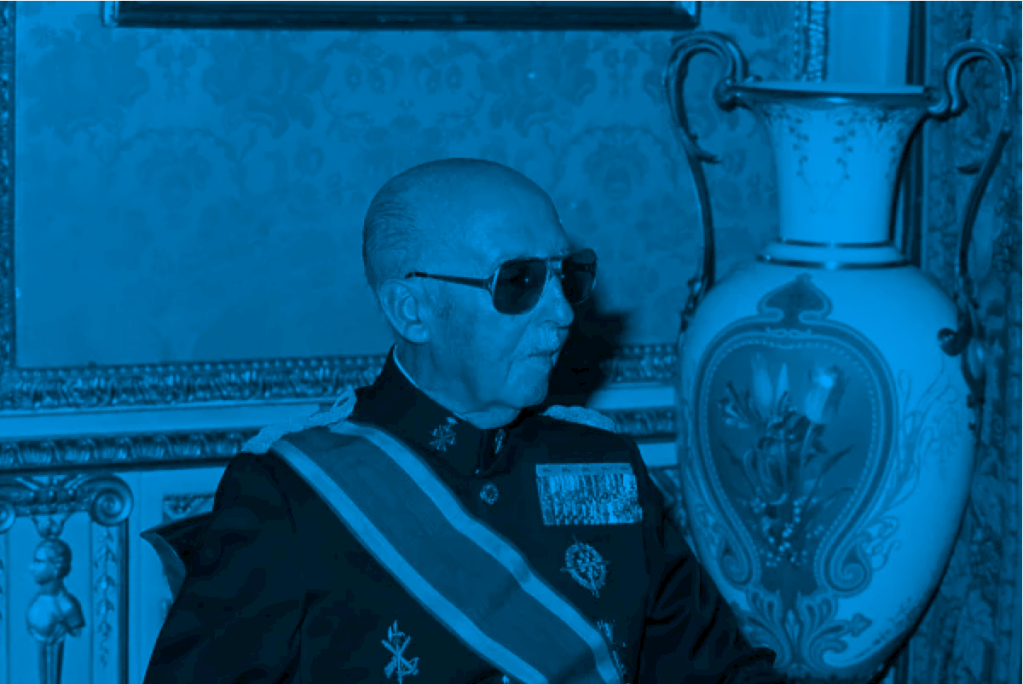

Spain in 1975 is a textbook case. By the time Francisco Franco died, his dictatorship looked like a relic of the past. A new generation had grown up in cities, studied in universities, worked in modern industries, and engaged with Europe culturally and economically. Yet the political order remained stuck, clinging to fascist eccentricities that no longer held meaning for the people it claimed to govern. Once Franco was gone, the system collapsed with astonishing speed. Soon after, Spain joined the European Economic Community, ratified the European Convention on Human Rights, and was welcomed in NATO. All in five years’ time. Society simply moved on not cautiously, but decisively, leaving the old machinery of repression to crumble under its own irrelevance.

Taiwan’s transformation followed the same pattern. It too had been ruled for decades by the Kuomintang, even as the island became one of the most dynamic societies in the Pacific. Its economy was relatively advanced, connected to the West, and accustomed to openness, while the political framework remained locked inside a brittle one-party structure. When the aging authoritarian leadership exited the stage, the shift was almost immediate. The public stepped into a democratic future that had already taken shape in everyday life. The old order, built on control, could not survive in a society that had long since outgrown it.

What happened in Spain and Taiwan gives a beacon of hope. Many countries today are governed by regimes outpaced by their own populations. They misread silence as consent, confuse fatigue for loyalty, and assume time is on their side. In parts of the Middle East and across Eurasia, we see aging leaderships presiding over young, rapidly changing societies, often without realizing how quickly the ground is shifting beneath them. Even in places much closer to home, the same structural tensions are gaining momentum, and the next transitions may arrive the same way: suddenly to outsiders, inevitable in retrospect.

The pace of such change is often incredible. Today, Spain and Taiwan stand as consolidated, confident democracies with highly liberal societies — a complete departure from what they were under authoritarian rule. Spain before 1975 and Spain after 1975 are barely recognizable as the same country in terms of politics, and Taiwan’s transition was just as dramatic. These cases show that when a society has already moved on, the political system can transform almost overnight. Democratic change is not an event but a realization: the moment a nation steps fully into the future it has long been preparing for.

Leave a comment