In The Narrow Corridor, Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson outline the fragile space in which liberty survives—between the overbearing hand of the state and the chaos of a lawless society. But there is another corridor, narrower still, navigated not by citizens but by autocrats. It is the corridor between personalization and institutionalization.

Authoritarian rulers are not all the same. Some hollow out institutions to tighten personal control; others build durable authoritarian bureaucracies that can outlive their founders. The tension is real—and the trade-offs are sharp. An autocrat who personalizes too much may secure loyalty but lose competence. An autocrat who builds institutions risks planting the seeds of intra-regime opposition.

The risks of personalization is particularly high. In the pursuit of total control, personalization corrodes the very institutions that make a state functional. Armies become parades of loyalty, not engines of defense. Central banks turn into tools of patronage, not stewards of monetary policy. The more personalized a regime becomes, the tighter the ruler’s grip—but the weaker the regime itself. Incapable institutions are a strategic vulnerability that actors external to the regime easily exploit.

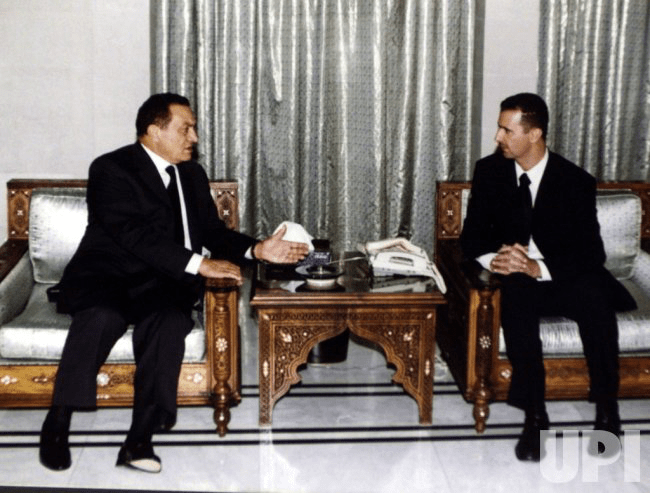

The collapse of Syria illustrates extreme personalization vividly. When Assad faced a nationwide uprising, his regime responded with unrestrained violence. But decades of personalization had hollowed out the state. His military and bureaucracy were staffed with family members. Assad survived for over a decade—only with the help of Iran and Russia. And when he was left to his own military resources, his regime fell in shockingly short time.

Too much institutionalization brings its own hazards. When institutions within authoritarian regimes become too autonomous, they begin to generate power centers that operate independently of the leader. This can lead to intra-regime coups, competing bureaucratic interests, and actors who may resist the dictator’s grip altogether. Institutionalized regimes can function more effectively, but they often render the leader replaceable. The more capable the system becomes, the more disposable its leader may appear.

Egypt is a good example—an institutional autocracy dominated by the military. Since Nasser, leaders have come and gone, but the military has stayed constant. Even Hosni Mubarak, who ruled for three decades, was ultimately discarded when he turned into a liability for the regime. So, the figureheads of autocracy are expendable; the system is not. In Egypt, personalization is discouraged not to preserve democracy but to keep the military in power. The corridor here is not toward liberalism but toward elite-managed authoritarian stability.

The irony is stark. In trying to eliminate threats, dictators often create them. Personalization produces regimes that are intensely loyal to the ruler but incapable of dealing with challenges. When the crisis hits, these regimes crumble quickly. On the other hand, institutionalization creates state organs that can deliver for the dictator, but their growing autonomy and capabilities are a constant source of suspicion. When a leader becomes a burden, institutions that make up the regime remove him and move on.

Acemoglu and Robinson’s original corridor reminds us that freedom requires tension—a constant pull between state and society. But dictatorships require tension too, of a different kind. The dictator must balance self-preservation with system survival. He must rule, but not destroy the apparatus of rule. That is the other narrow corridor—and few manage to walk it for long.

Leave a comment